Risk of Sub-Par Monsoon and drought Over India Rises in 2026

Key Takeaways:

- Climate models indicate a likely El Niño developing in the second half of 2026.

- An evolving El Niño poses a higher risk of suppressed monsoon rainfall over India.

- Breakdown of La Niña will trigger a major Pacific shift influencing global weather.

- El Niño-linked rainfall deficits could impact agriculture, food production, and inflation.

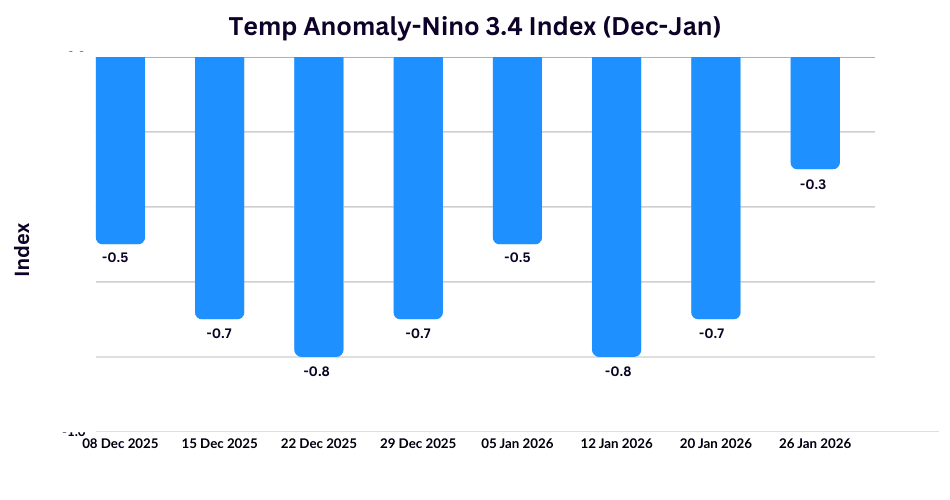

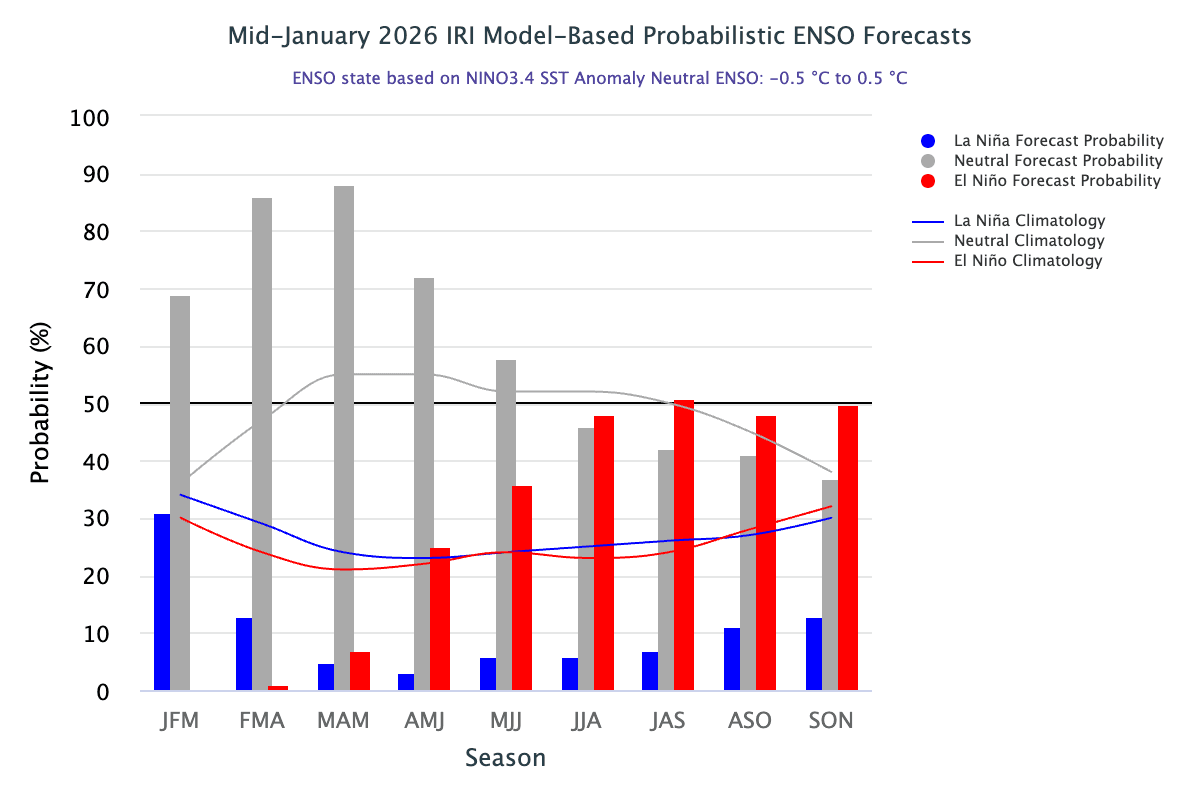

Climate models are showing early signs of a likely El Niño developing in the year 2026. The equatorial Pacific Ocean is indicating a return of El Niño, raising fears of impending adverse weather activity across many parts of the globe. Latest forecast data shows that an El Niño could begin in the second half of 2026, pick up strength in the middle of the Indian monsoon, and peak during the Northern Hemisphere winter. Such a development heightens the risk of weather variability, more severely over South Asia, suppressing monsoon rainfall over India.

El Niño significantly disrupts global weather by shifting rainfall patterns, causing droughts in vulnerable regions such as Australia, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. Skymet was the first weather agency to break the unsettling news of an evolving El Niño during the Indian Monsoon 2026. Many other weather bodies have now joined to substantiate and support this claim. The apex body APCC has expressed fears that drought-bearing El Niño weather is likely to emerge towards July this year. This will affect the quantum of rainfall the country receives between June and September.

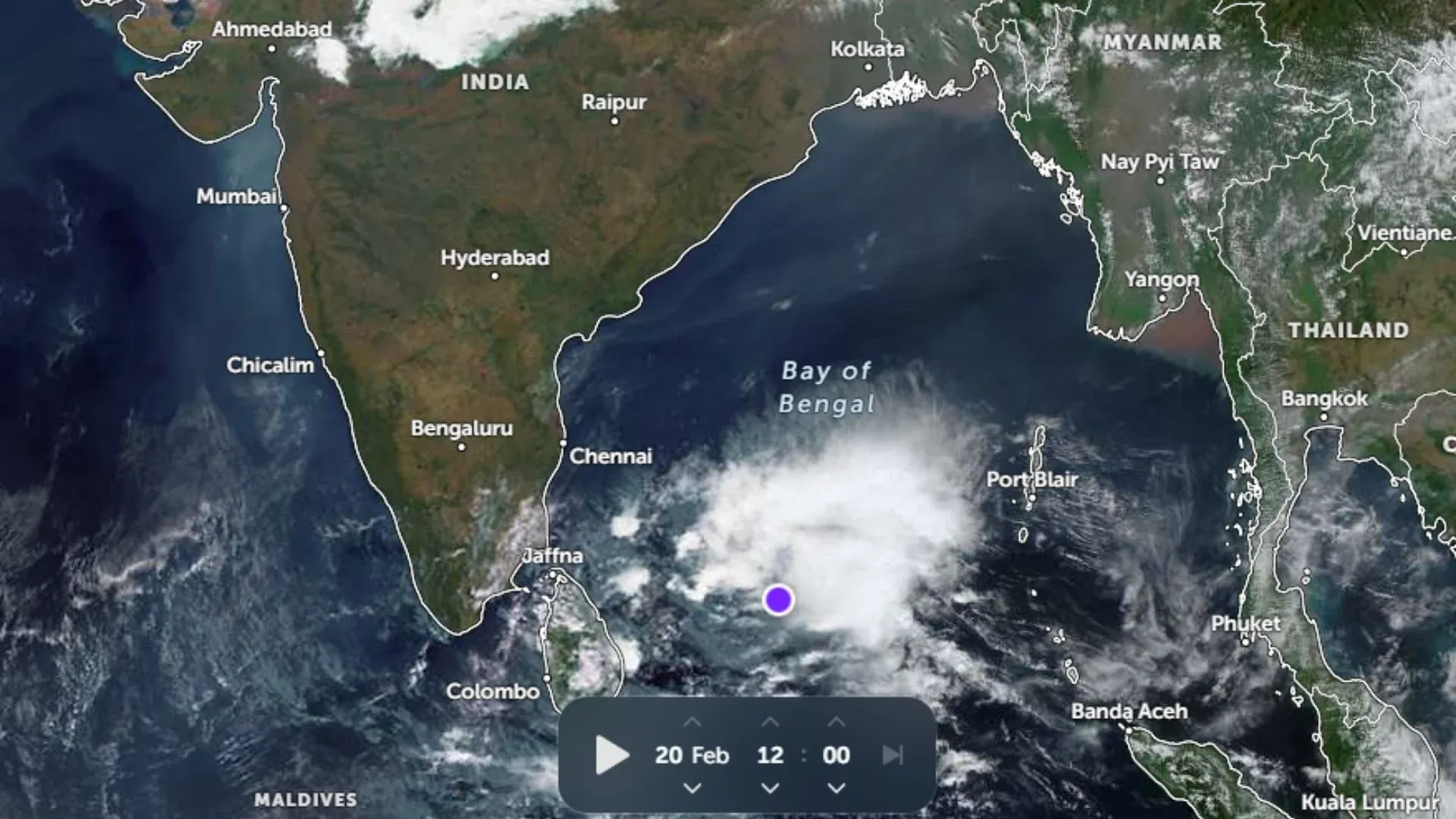

The ongoing La Niña has begun to break down across the tropical Pacific Ocean. The atmospheric influence is expected to continue till early spring, and ENSO-neutral conditions are likely during the summer months. The La Niña collapse will initiate a major Pacific flip, reshaping the global weather pattern of 2026.

An evolving El Niño had earlier corrupted the Indian monsoon in 2014 and 2018. The 2014 season ended in a drought, while 2018 escaped with a thin margin. In 2023, El Niño broke out in June and persisted for an extended period of eleven months, impacting the Indian monsoon. It also prompted 2024 to become the warmest year on record, as the phenomenon continued until April 2024. This resulted in food grain crops, particularly paddy and pulses, being affected, leading to lower production. In turn, this triggered food inflation during the period.

More than a full-blown El Niño, what is more worrisome is an evolving El Niño, which has a 60% chance of causing “below-normal” rainfall. An evolving El Niño can delay the monsoon arrival and subsequently vitiate the spatial and temporal distribution of monsoon rainfall. Quite often, it also leads to an increase in the frequency, intensity, and duration of heat waves. Consequently, it may adversely impact the country’s agricultural production, which may later run the risk of triggering food insecurity.

The persistent rise in global temperatures has introduced climate variability. The overpowering factor of human-induced climate warming has altered ENSO cycles as well. Frequent occurrences of El Niño and La Niña have become the new normal. In the last decade, since 2014, India has witnessed four El Niño and five La Niña events, against their normal frequency of one in 2–7 years.

Amid the increased threat of chaotic events like El Niño, the National Weather Agency has introduced another predicament. The India Meteorological Department has abolished the use of the term “drought,” which was earlier used effectively during El Niño-triggered desiccation events. In January 2016, the department officially replaced the term “drought” with “deficient.” The sense of seriousness and alarm associated with “drought” appears to have been compromised, and its use now remains shrouded.

The National Weather Service decided to drop the term because defining drought was considered outside its purview, and the announcement of drought was passed on to the respective states as a regional responsibility. The India Meteorological Department, being the sole custodian and repository of the countrywide rainfall data, should have the prerogative of declaring drought. The states are not adequately equipped and lack the infrastructure and resources to analyse cumbersome rainfall data. It is strongly felt that IMD should resume the earlier procedure, which is practiced by most other countries.

Trending: Evolving El Nino To Keep Monsoon At Risk