La Nina Advisory Continue: ENSO-Neutral Likely During Spring Barrier

Key Takeaways:

- Global sea level rise slowed sharply in 2025 due to persistent La Niña cooling.

- Sea surface height reflects ocean heat content and ENSO intensity across the Pacific.

- La Niña conditions may continue through February despite index fluctuations.

- Climate models suggest rising El Niño chances after June with possible monsoon impact.

Sea surface height is a function of temperature, and therefore the mean sea level varies across oceans from one region to another. The tropics are generally warmer, so the volume of water expands and raises the sea level. ENSO events such as El Niño and La Niña trigger warming and cooling cycles in the tropical Pacific Ocean. The variation in sea level becomes a measure of the intensity of El Niño or La Niña. Sea level is naturally higher in the Western Pacific, and a rise of 40–50 cm is normally noticed near Indonesia compared with Ecuador on the eastern flank. Some of this difference is due to tropical trade winds, which predominantly blow from east to west across the Pacific Ocean, accumulating warm waters near Asia and Oceania. Part of it is also due to heat stored in the water column beneath the sea surface. The height of the sea surface provides a good approximation of the heat content of the water.

The rise in global mean sea level slowed in 2025 relative to the previous year, largely due to La Niña conditions that persisted through most of the year. According to a NASA analysis, the average ocean height increased by 0.03 inches in 2025, down from 0.23 inches in 2024. The 2025 figure also fell below the long-term expected rate of 0.17 inches per year based on the rate of rise since the early 1990s. The cooling effect tends to diminish sea level rise. The current La Niña has been relatively mild. However, when set against human-induced climate warming, the drop in sea level due to La Niña was partly neutralized. The combined effect of the two factors—one tending to lower sea level and the other tending to increase it—resulted in an average rise in 2025 that was lower than the long-term mean rate.

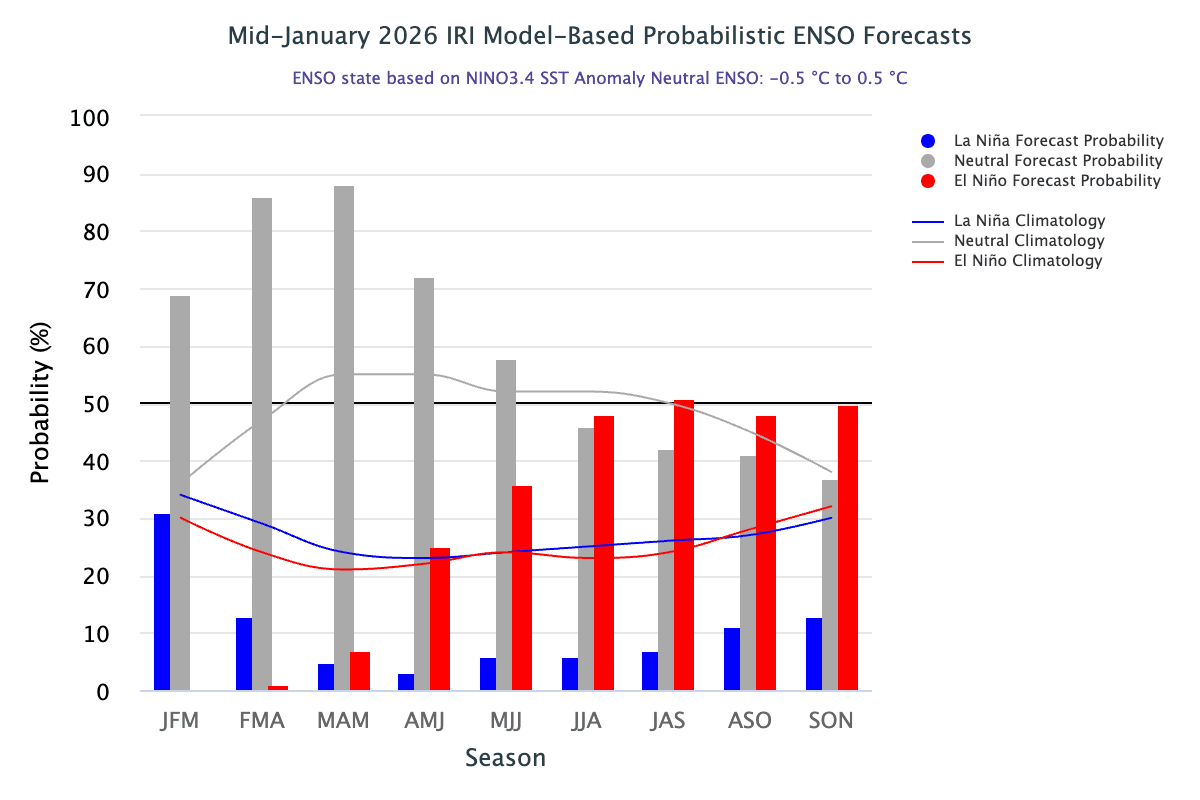

ENSO: The latest climate models show a greater than 50% chance of El Niño developing after June over the Indian region, increasing to nearly 70% during July–August–September. However, the spring predictability barrier makes February–March forecasts less reliable and they should be treated with caution. Even so, evolving El Niño conditions have disrupted the Indian monsoon on more than one occasion over the past decade.

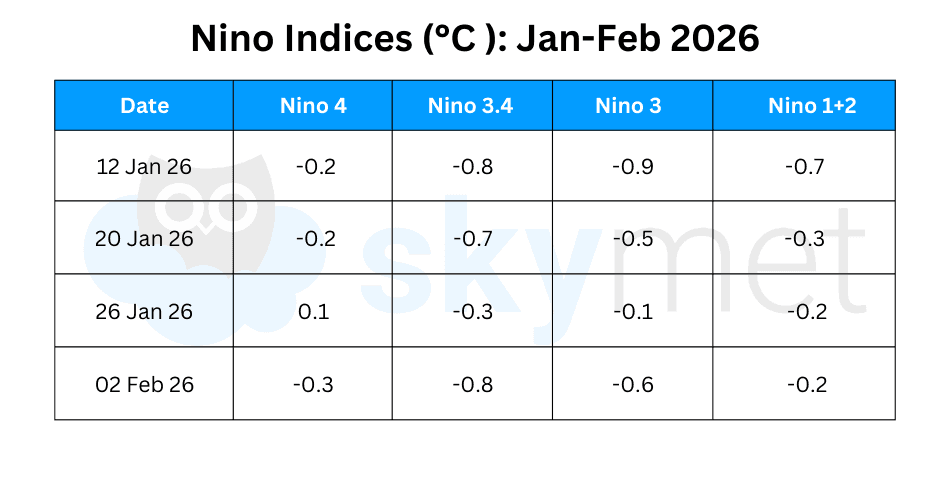

Niño indices had dropped sharply last week but have since rebounded, supporting the continuation of La Niña conditions. Niño-3.4 has again reached −0.8°C, its lowest mark of the season. This indicates that Pacific cooling is not yet complete and may persist through February.

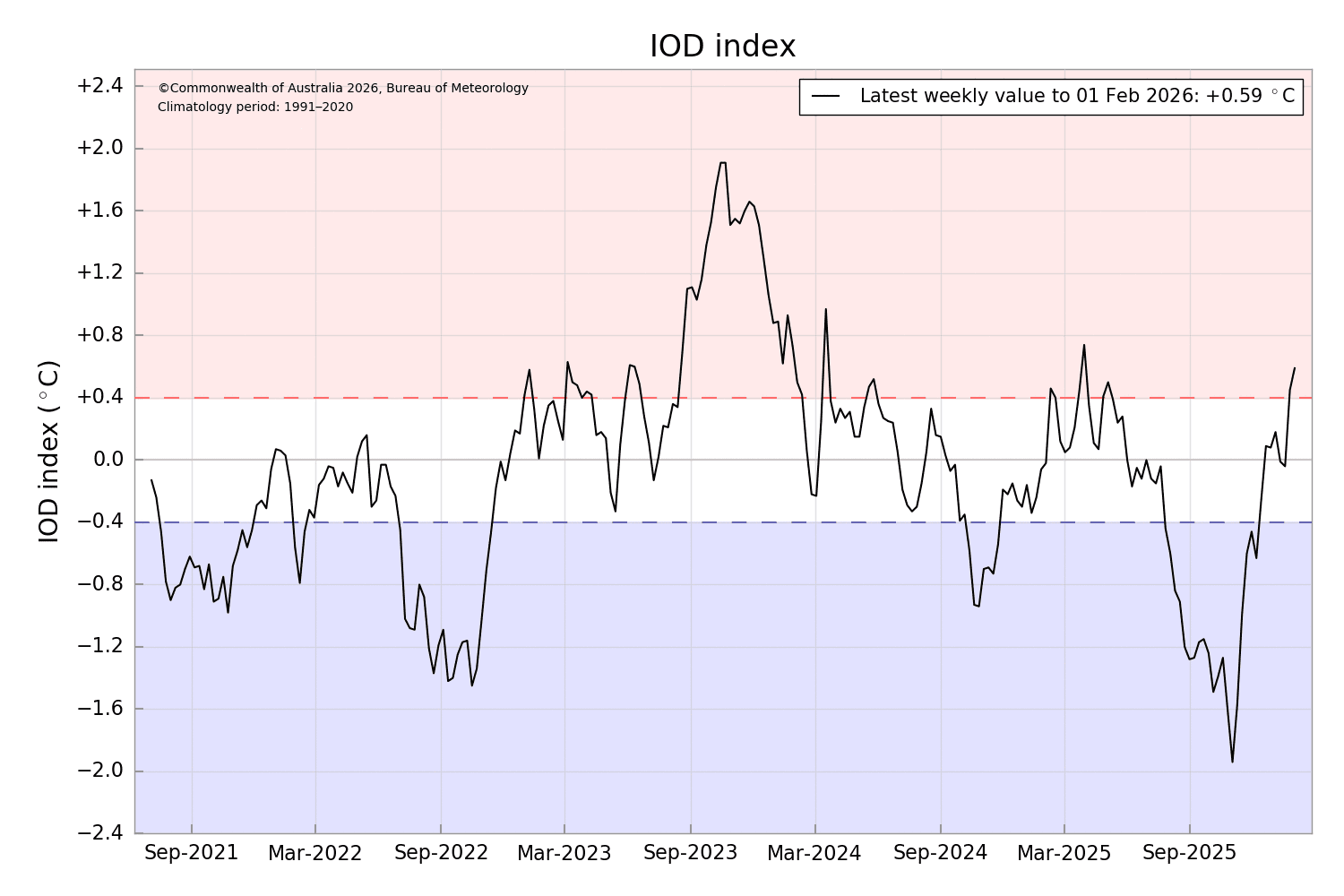

IOD: While the Pacific remains cooler than average, the western equatorial Indian Ocean has warmed significantly. The Indian Ocean departure is positive and has remained above the +0.4°C threshold for the second consecutive week. The index value for the week ending 01 February 2026 was +0.59°C, the highest positive value since March 2025. Models still support a neutral IOD during February–March–April 2026.

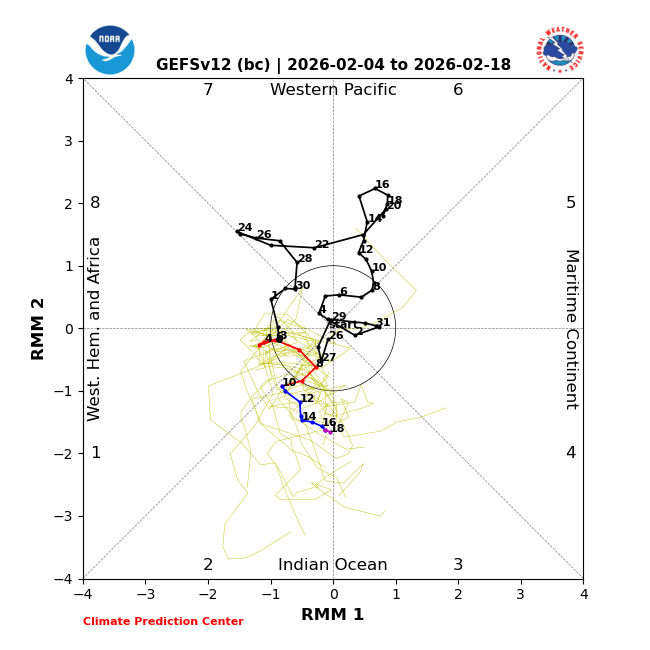

MJO: There is considerable uncertainty regarding the location, amplitude, and progression of the MJO. Dynamical models indicate a weak or stagnant MJO initially, with emergence over the Indian Ocean in Phases 2 and 3 during the third week of February. However, MJO phases 1–3 and the La Niña base state are typically considered to be at odds, and the MJO may act to suppress La Niña conditions. The southern Indian Ocean remains highly active, with a few invest areas to watch for possible intensification.

Large fluctuations in Niño indices may be linked to the spring predictability barrier. The indices could remain inconsistent for a few more weeks before stabilizing. A steady-state equatorial Pacific Ocean is required before declaring the end of La Niña.